Curaçao conceals tales of conquests, forced labour and struggle. It is an island’s history that breathes spirit into the future of its people and in Curaçao the people’s history is deeply rooted to the legends of their past.

Curaçao conceals tales of conquests, forced labour and struggle. It is an island’s history that breathes spirit into the future of its people and in Curaçao the people’s history is deeply rooted to the legends of their past.

Curaçao, pronounced “cure a sow”, was discovered in 1499 by the Spanish explorer Alonso de Ojeda accompanied by the Italian Amerigo Vespuci. The history of Curaçao however begins with the Caiquetios subgroup of the Arawak Indians, migrating to the island from the South American mainland some 6000 years ago. The Caiquetios lived a prolific life of fishing, food collection and trade with neighbouring islands and the mainland tribes. All in all a happy life, until the arrival of the first Spanish colonists and the discovery of the island by the Ojeda expedition.

By 1513 Curaçao and neighboring Aruba and Bonaire were declared “Islas Inutiles” (useless Islands) after depleting the little gold there was and finding the water sources insufficient for farming. This announcement by the Spanish also meant deportation for the surviving 2000 Indians to Hispanola where they were to work as slaves.

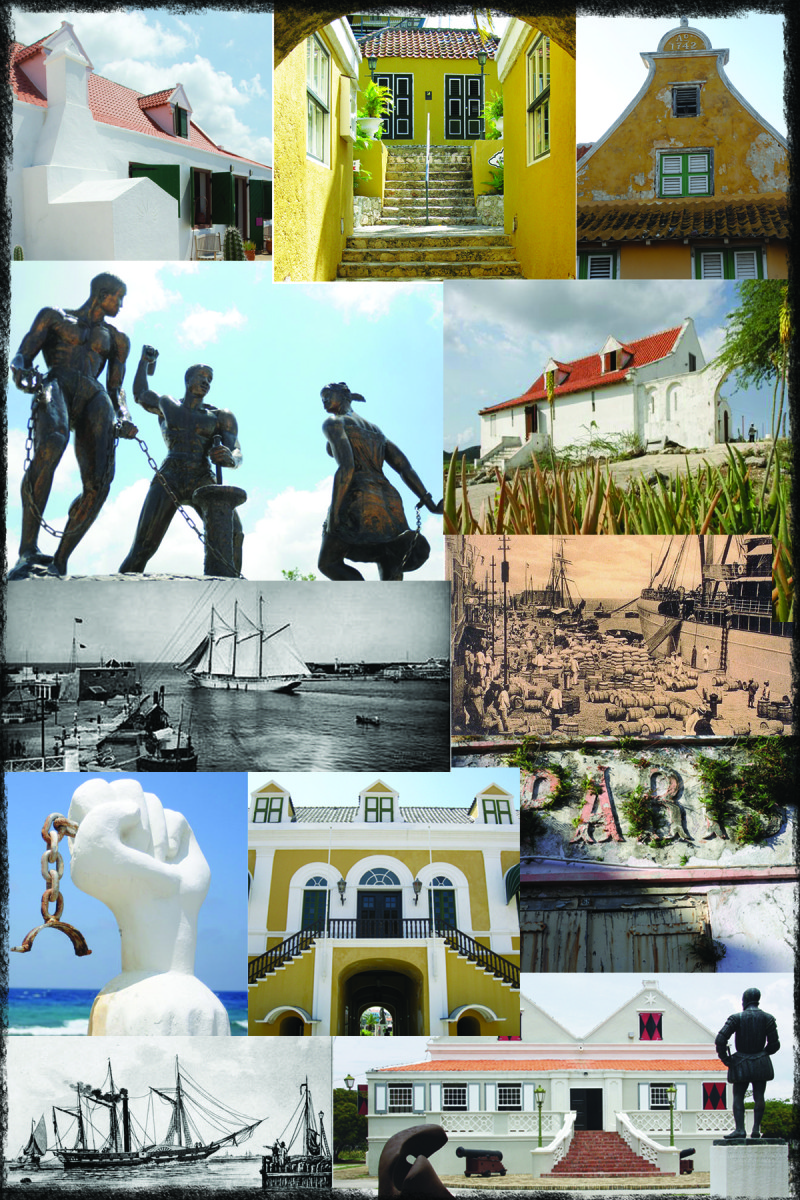

In 1634, there was only a motley group of Spanish remaining on the island. The Dutch West India company (W.I.C) then saw an opportunity and took over the island without too much resistance. The W.I.C promptly founded the capital of Willemstad on the bank of the inlet called Schottegat. This inlet is now called the St. Annabaai. Willemstad became a fortified port town with the construction of Punda. Inner districts of the city named Otrobanda, Pietermaai and Scharloo Otrobanda, were formed in later centuries and today represent the inner city of the capital.

Curaçao previously ignored by colonists due to the deficiency in many things such as gold, possessed however a deep natural harbour that became a superlative site for trade. From the early 16th century onward, Curaçao had a bustling and growing trade of sugar and salt. By 1662, Dutch merchants brought slaves from Africa to Curaçao and the island served as a slave depot for the region, with half the slaves destined for the Caribbean or South America.

Curaçao’s rich and sensitive cultural heritage is on display in its historic sites and in its museums. After a visit to the Curaçao Museum housed in a colonial-style building holding an amazing variety of treasures, or the Kura Hulanda Museum, where Dutch entrepreneurs once traded and transshipped enslaved Africans along with other “commercial goods”, or the Mongui Maduro Library, the plantation house of “Rooi Catootje” where time stands still; it is impossible not to be overwhelmed by a sense of deep-rooted history.

Dating back as far as the early 17th century to as late as the19th century, landhuizen were the houses of the landowners, and formed the epicenter of their plantation farms.

One cannot be less than impressed by the grandeur of these historic heritage houses. Throughout this island lie dozens of scattered colonial homes, uniquely built, varying in size and contrasting states of both remarkable renovation and eerie dilapidation.

The Landhuizen were built from coral, brick and stone details. Surrounding the main house were the slave huts and storage houses. They were situated mostly on hilltops so that lands, workers, and neighboring houses were within sight. The high saddle roofs built with Dutch tile were designed to catch and collect much needed rain water.

Two extraordinary men rose up and influenced the course of history; the white man Luis Brión, son of Dutch merchant Pedro and his wife Maria Detrox, and the black man Tula who led the slave revolt on the 17th of August 1795. Slavery was abolished in 1863. The 17th of is still celebrated in Curaçao to commemorate the beginning of a long fight for freedom. There is a monument to Tula and the rebel slaves on the south coast of Curaçao, between “Koredo” the Holiday Beach Hotel, the site where Tula was executed in the name of freedom from slavery.

Most of the slave houses that surrounded the property are long gone, but some of the former slave quarters in the style reminiscing western Africa, called “kas di pal’ maishi” (literally maize stalk house) have been restored and are now open to the public.

Landhuis Jan Kok built in 1654, is the oldest plantation house on the island. It sits facing the St. Marie salt flats and housed salt mining production in the 1800’s.

These exquisitely renovated beauties now serve as private homes, boutique hotels, restaurants, rehabilitations centers, law offices, art galleries and museums.Grab the local road map and drive around this colorful island to discover these architectural gems.